.png)

Abstract

Society faces multiple sustainability challenges. The transition towards a sustainable and inclusive economy requires rethinking and reorganising many current practices. Companies play an important role in that transition because social and environmental impacts are generated primarily in the corporate sector. Some companies will survive the transition by providing valuable solutions; others will not, as their competitive positions are eroded. Sustainability is therefore also about corporate survival. Responsible companies are increasingly adopting the goal of integrated value creation, which unites financial, social, and environmental value.

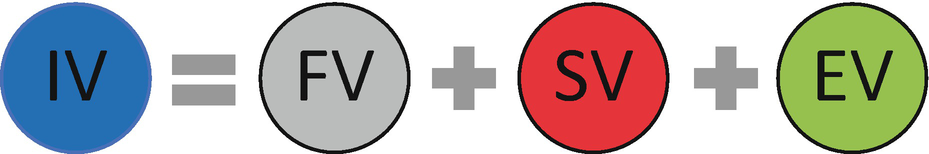

This raises the fundamental question in corporate finance: what is the objective of the company? The traditional objective is maximising profit, which boils down to maximising financial value for shareholders. This does not incentivise companies to act in a sustainable manner. An alternative view is to broaden the objective of the company to optimising integrated value (IV) for all stakeholders, which combines financial value (FV), social value (SV), and environmental value (EV). Applying this new paradigm of integrated value is the real innovation of this corporate finance textbook.

Overview

Society faces multiple sustainability challenges. On the environmental front, climate change, land-use change, biodiversity loss, freshwater shortages, and depletion of natural resources are destabilising the Earth system. On the social side, many people are afflicted by poverty, hunger, and lack of healthcare. Sustainability means that current and future generations have the resources needed, such as food, water, healthcare, and energy, without stressing the Earth system processes. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a guide for the transition towards a sustainable and inclusive economy.

Companies play an important role in that transition to a sustainable economy because social and environmental impacts are generated primarily in the corporate sector. Some companies will survive the transition by providing valuable solutions; others will not, as their competitive positions are eroded. Sustainability is therefore also about corporate survival. Responsible companies are increasingly adopting the goal of integrated value creation, which unites financial, social, and environmental value.

This raises the fundamental question in corporate finance: what is the objective of the company? The traditional objective is maximising profit, which boils down to maximising financial value for shareholders. This does not incentivise companies to act in a sustainable manner. An alternative view is to broaden the objective of the company to optimising integrated value (IV), which combines financial value (FV), social value (SV), and environmental value (EV). Figure 1.1 depicts the new paradigm of integrated value. In that way, the interests of current and future stakeholders are equal and aligned with sustainable development. Applying this new paradigm of integrated value is the real innovation of this corporate finance textbook.

This integrated approach to value has profound implications for corporate finance. It challenges conventional thinking and practices regarding various aspects of financial decision-making, including corporate investments, valuation, and capital structure.

Learning Objectives

After you have studied this chapter, you should be able to:

-

Analyse the planet’s social and environmental challenges

-

Identify and interpret the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

-

Define the transition towards a sustainable world

-

Critically review the objective of the company

-

Demonstrate the concept of integrated value

-

Identify the challenges of incorporating sustainability into corporate finance

1.1 Social and Planetary Boundaries in a Full World

Our economic models were developed in an empty world, with an abundance of goods and services produced by nature (Daly & Farley, 2011). These models assumed that labour and capital were the scarce production factors to optimise in economic production, while nature and its services were freely available. Human society became dependent on fossil fuels and other non-renewable resources. Technological advances allowed the unprecedented production of consumer goods, spurring economic and population growth. Urbanisation led to a reduction in arable land, driving further deforestation.

More recently, we have started to realise that natural resources are finite. In the early 1970s, the Club of Rome warned that the Earth system cannot support our rates of economic and population growth much beyond 2100. Its report Limits to Growth argues that humankind can create a society in which it lives indefinitely on earth. This requires a balance between population and production, for which humankind needs to impose limits on its production of material goods (Meadows et al., 1972).

Another step in awareness was the United Nations’ (UN) Brundtland Report (1987), which argues that ‘...the environment is where we live; and development is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that environment. The two are inseparable’. The report defines sustainable development as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. The Brundtland report stresses that sustainability is about the future.

Climate change is one of the largest environmental risks affecting society. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is an international environmental treaty. Since 1995, it has been organising Conferences of the Parties (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change. In the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change (COP21), countries reconfirmed the target of limiting the rise in global average temperatures relative to those in the preindustrial world to 2 °C (two degrees Celsius) and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C (UNFCCC, 2015). Achieving this would ensure that the stock of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere does not exceed a certain limit. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023) estimates that the remaining carbon budget amounts to 1150 gigatonnes of CO2 from 2020 onwards (for a probability of 67% for limiting global warming to 2 °C). If current global carbon emissions (approximately 40 gigatonnes a year) are not drastically cut, the 2 °C limit would be reached around the year 2048.Footnote1

The most pressing environmental and social challenges include climate risk, land-system change, biodiversity loss, green water, nitrogen and phosphorus flows, poverty, food, and health problems. Our economic system creates these environmental and social impacts on society; they are inseparable from production decisions. To highlight the tension between unbridled economic growth and sustainable development, we provide two examples. Box 1.1 describes the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Box 1.2 illustrates the impact of the collapse of a factory building in Bangladesh. Both examples involve an underinvestment in safety to increase short-term profits.

Box 1.1: The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Oil began to spill from the Deepwater Horizon drilling platform on 20 April 2010, in the BP-operated Macondo Prospect in the Gulf of Mexico. An explosion on the drilling rig led to the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. The US Government estimated the total discharge at 4.9 million barrels.

A massive response ensued to protect beaches, wetlands, and estuaries from the spreading oil. Oil clean-up crews worked on 55 miles of the Louisiana shoreline until 2013. The months-long spill caused extensive damage to marine and wildlife habitats and the fishing and tourism industries.

Investigation pointed to defective cement on the well, laying the fault mostly with BP, but also with rig operator Transocean and contractor Halliburton. In 2011, a National Commission (2011) likewise blamed BP and its partners for a series of cost-cutting decisions and an inadequate safety system; it also concluded that the spill resulted from ‘systemic’ root causes and that without ‘significant reform in both industry practices and government policies, might well recur’.

Box 1.2: Rana Plaza Factory Collapse

The Rana Plaza collapse was a disastrous structural failure of an eight-storey commercial building on 24 April 2013 in Bangladesh. The collapse of the building caused 1129 deaths, while approximately 2500 injured people were rescued alive from the building. It is considered the deadliest garment factory accident in history and the deadliest accidental structural failure in modern human history.

The building contained clothing factories, a bank, apartments, and several shops. The shops and the bank on the lower floors were immediately closed after cracks were discovered in the building. The building’s owners ignored warnings to evacuate the building after cracks in the structure appeared the day before the collapse. Garment workers, earning €38 a month, were ordered to return the following day, and the building collapsed during the morning rush-hour.

The factories manufactured clothing for brands including Benetton, Bonmarché, the Children’s Place, El Corte Inglés, Joe Fresh, Monsoon Accessorize, Mango, Matalan, Primark, and Walmart.

1.1.1 Planetary Boundaries

There can be no Plan B, because there is no Planet B.

Former United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon

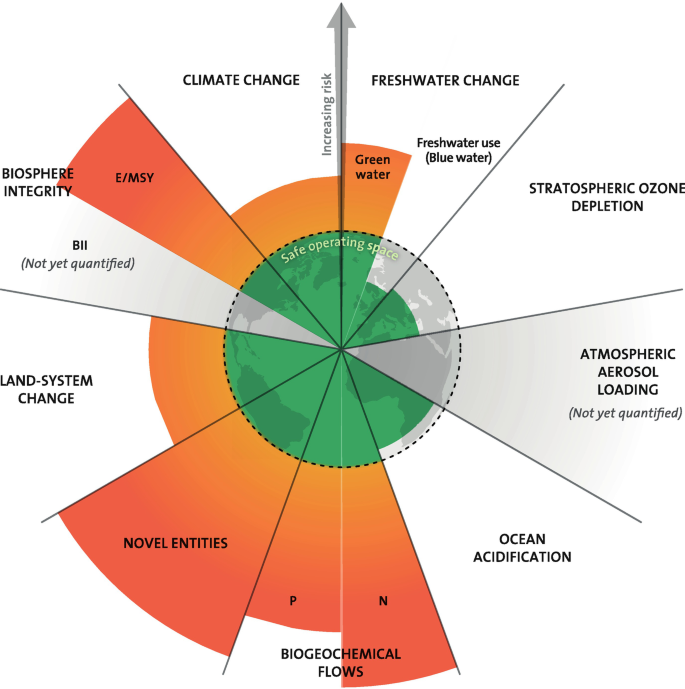

There is increasing evidence that human activities are affecting the Earth system, threatening the planet’s future liveability. The planetary boundaries framework of Steffen et al. (2015) defines a safe operating space for humanity within the boundaries of nine productive ecological capacities of the planet. The framework is based on the intrinsic biophysical processes that regulate the stability of the Earth system on a planetary scale. The green zone in Fig. 1.2 is the safe operating space; orange represents the zone of uncertainty (increasing risk) and red (dark orange) indicates the zone of high risk. Table 1.1 specifies the control variables and quantifies the ecological ceilings.

The planetary boundaries. Source: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Persson et al. (2022), Steffen et al. (2015), and Wang-Erlandsson et al. (2022)

Table 1.1 The ecological ceiling and its indicators of overshoot

From: The Company within Social and Planetary Boundaries

|

Earth system pressure |

Control variable |

Planetary boundary |

Current value and trend |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Climate change |

Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration; parts per million (ppm) |

At most 350 ppm |

420 ppm and rising (worsening) |

|

Biosphere loss |

Genetic diversity: rate of species extinction per million species per year |

At most 10 |

Around 100–1000 and rising (worsening) |

|

Functional diversity: biodiversity intactness index (BII) |

Maintain BII at 90% |

84% applied to southern Africa only |

|

|

Land-system change |

Area of forested land as a proportion of forest-covered land prior to human alteration |

At least 75% |

62% and falling (worsening) |

|

Freshwater change |

Green water: percentage of ice-free land area on which root-zone soil moisture is too low (or too high) |

– |

– |

|

Blue water consumption; cubic kilometres per year |

At most 4000 km3 |

Around 2600 km3 and rising (intensifying) |

|

|

Biochemical flows |

Phosphorus applied to land as fertiliser; millions of tons per year |

At most 6.2 million tons |

Around 14 million tons and rising (worsening) |

|

Reactive nitrogen applied to land as fertiliser; millions of tons per year |

At most 62 million tons |

Around 150 million tons and rising (worsening) |

|

|

Ocean acidification |

Average saturation of aragonite (calcium carbonate) at the ocean surface, as a percentage of preindustrial levels |

At least 80% |

Around 84% and falling (intensifying) |

|

Air pollution |

Aerosol optical depth (AOD); much regional variation, no global level yet defined |

– |

– |

|

Ozone layer depletion |

Concentration of ozone in the stratosphere; in Dobson Units (DU) |

At least 275 DU |

283 DU and rising (improving) |

|

Novel entities |

Production volume of plastics |

– |

– |

|

Production volume of hazardous chemicals |

– |

– |

- Source: Updated from Persson et al. (2022), Steffen et al. (2015), and Wang-Erlandsson et al. (2022)

Applying the precautionary principle, the planetary boundary itself lies at the intersection of the green and orange zones. To illustrate how the framework works, we look at the control variable for climate change, the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases. The zone of uncertainty ranges from 350 to 450 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide. We crossed the planetary boundary of 350 ppm in 1988, with a level of 420 ppm in early 2023 (see Table 1.1). The upper limit of 450 ppm is consistent with the goal (at a fair chance of 67%) to limit global warming to 2 °C above the preindustrial level and lies at the intersection of the orange and red zones.

Another example in the orange zone of increasing risk is land-system change. The control variable is the area of forested land as a proportion of forest-covered land prior to human alteration. The planetary boundary is at 75% (safe minimum), while we are currently at 62%, and the percentage is falling (worsening).

The current linear production and consumption system is based on the extraction of raw materials (take), processing them into products (make), consumption (use), and disposal (waste). Traditional business models centred on a linear system assume the on-going availability of unlimited and cheap natural resources. This is increasingly risky because non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels, minerals, and metals, are increasingly under pressure, while potentially renewable resources, such as forests, rivers, and prairies, are declining in their extent and regenerative capacity.

Moreover, the use of fossil fuels in the linear production and consumption system overburdens the Earth system as a natural sink (absorbing pollution). Baseline scenarios (i.e., those without mitigation) for climate change result in global warming in 2100 at approximately 3.0 °C compared to the preindustrial level (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023). Furthermore, food production leads to biodiversity loss because of the conversion of natural forests to agriculture (land-system change).

With this linear economic system, we are crossing planetary boundaries beyond which human activities might destabilise the Earth system. In particular, the planetary boundaries of climate change, land-system change (deforestation and land erosion), biodiversity loss (terrestrial and marine), green water (needed for vegetation), novel entities (plastics and chemicals), and biochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus, mainly because of intensive agricultural practices) have been crossed (see Fig. 1.2). A timely transition towards an economy based on sustainable production and consumption, including the use of renewable energy, reuse of materials and land restoration, can mitigate these risks to the stability of the Earth system.

1.1.2 Social Foundations

Mass production in a competitive economic system has led to long working hours, underpayment, and child labour, first in the developed world and later relocated to the developing world. Human rights provide the essential social foundation for all people to lead lives of dignity and opportunity. Human rights norms assert the fundamental moral claim each person has to life’s essential needs, such as food, water, healthcare, education, freedom of expression, political participation, and personal security. Raworth (2017) defines the social foundations as the twelve top social priorities, grouped into three clusters, focused on enabling people to be:

- 1. Well: through food security, adequate income, improved water and sanitation, housing and healthcare

- 2. Productive: through education, decent work, and modern energy services

- 3. Empowered: through networks, gender equality, social equity, political voice, and peace and justice

While these social foundations only set out the minimum of every human’s claims, sustainable development envisions people and communities prospering beyond this, leading lives of creativity and thriving. Sustainable development combines the concept of planetary boundaries with the complementary concept of social foundations or boundaries (Sachs, 2015). Sustainability means that current and future generations have the resources needed, such as food, water, healthcare and energy, without stressing processes within the Earth system.

Many people are still living below the foundational social boundaries of no hunger, no poverty (a minimum income of $2.15 a day), access to education and access to clean cooking facilities (see Table 1.2). Political participation, which is the right of people to be involved in decisions that affect them, is a basic value of society. The UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world’. Decent work can lift communities out of poverty and underpins human security and social peace. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (see Sect. 1.2 below) places decent work for all people at the heart of policies for sustainable and inclusive growth and development. Decent work has several dimensions: a basic living wage (which depends on a country’s basket of basic goods), no discrimination (e.g. gender, race, or religion), no child labour, health and safety, and freedom of association.

Table 1.2 The social foundation and its indicators of shortfall

From: The Company within Social and Planetary Boundaries

|

Dimension |

Illustrative indicator (per cent of global population unless otherwise stated) |

% |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Food |

Population undernourished |

11 |

2014–16 |

|

Health |

Population living in countries with under-five mortality rate exceeding 25 per 1000 live births |

46 |

2015 |

|

Population living in countries with life expectancy at birth of less than 70 years |

39 |

2013 |

|

|

Education |

Adult population (aged 15+) who are illiterate |

15 |

2013 |

|

Children aged 12–15 out of school |

17 |

2013 |

|

|

Income and work |

Population living on less than the international poverty limit of $2.15 a day |

29 |

2012 |

|

Proportion of young people (aged 15–24) seeking but not able to find work |

13 |

2014 |

|

|

Water and sanitation |

Population without access to improved drinking water |

9 |

2015 |

|

Population without access to improved sanitation |

32 |

2015 |

|

|

Energy |

Population lacking access to electricity |

17 |

2013 |

|

Population lacking access to clean cooking facilities |

38 |

2013 |

|

|

Networks |

Population stating that they are without someone to count on for help in times of trouble |

24 |

2015 |

|

Population without access to the Internet |

57 |

2015 |

|

|

Housing |

Global urban population living in slum housing in developing countries |

24 |

2012 |

|

Gender equality |

Representation gap between women and men in national parliaments |

56 |

2014 |

|

Worldwide earnings gap between women and men |

23 |

2009 |

|

|

Social equity |

Population living in countries with a Palma ratio of 2 or more (the ratio of the income share of the top 10% of people to that of the bottom 40%) |

39 |

1995–2012 |

|

Political voice |

Population living in countries scoring 0.5 or less out of the 1.0 in the Voice and Accountability Index |

52 |

2013 |

|

Peace and justice |

Population living in countries scoring 50 or less out of 100 in the Corruption Perceptions Index |

85 |

2014 |

|

Population living in countries with a homicide rate of 10 or more per 10,000 |

13 |

2008–13 |

- Source: Updated from Raworth (2017) and World Bank

From a societal perspective, it is important for business to respect these social foundations and to ban underpayment, child labour, and human rights violations. Social regulations have been introduced in developed countries, but violations still occur in developing countries. A case in point is the use of child labour in factories in developing countries producing consumer goods, such as clothes and shoes, to be sold by multinational companies in developed countries. These factories often lack basic worker safety features (Box 1.2). Another example is the violation of the human rights of indigenous peoples, often in combination with land degradation and pollution, by extractive companies in the exploration and exploitation of fossil fuels, minerals, and other raw materials.

1.2 Sustainable Development Goals

To guide the transition towards a sustainable and inclusive economy, the United Nations has developed the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015). This includes the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to stimulate action over the period of 2015–2030 in areas of critical importance for humanity and the planet. Box 1.3 explains the SDGs.

Box 1.3: The Sustainable Development Goals

The following are the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2015):

Economic Goals

-

Goal 8. Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

-

Goal 9. Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation, and foster innovation

-

Goal 10. Reduce inequality within and among countries

-

Goal 12. Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Societal Goals

-

Goal 1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere

-

Goal 2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture

-

Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

-

Goal 4. Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

-

Goal 5. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

-

Goal 7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all

-

Goal 11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable

-

Goal 16. Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels

Environmental Goals

-

Goal 6. Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

-

Goal 13. Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

-

Goal 14. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development

-

Goal 15. Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

Overall Goal

-

Goal 17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development

To facilitate implementation, the 17 high-level goals are specified in 169 targets (see https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals).

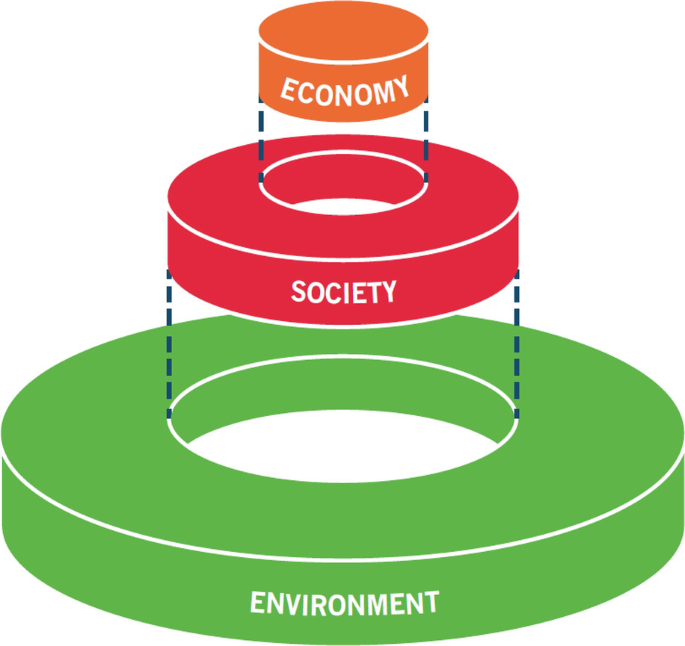

Following Rockström and Sukhdev (2016), we classify the SDGs according to several levels: the economy, society, and environment (Fig. 1.3). Nevertheless, we stress that the SDGs are interrelated. A case in point is the move to sustainable consumption and production (Economic Goal 12) and sustainable cities (Societal Goal 11), which are instrumental to combat climate change (Environmental Goal 13). Another example is appropriate income and decent work for all (Economic Goal 8), which is instrumental in attaining Societal Goals 1–4. Through a living wage, households can afford food, healthcare, and education for their family.

Sustainable development challenges at different levels. Source: Adapted from Rockström and Sukhdev (2016)

1.2.1 Global Strategy

The UN SDGs are the global strategy of governments under the auspices of the United Nations and provide direction towards (future) government policies, such as the regulation and taxation of environmental and social challenges. This strategy is boosted by technological change (e.g. the development of solar and wind energy and electric cars at decreasing cost or the development of drip irrigation systems), which supplements government policies (e.g. carbon pricing or water pricing). Some companies are preparing for this transition (future makers) and are part of the solution (Mercer, 2015). Other companies are waiting for the transition to unfold before acting (future takers). A final category of companies is unaware of this transition and continues business as usual.

We, as authors, attach a positive probability to the scenario that the SDGs are largely met. Our observation is based on the success of the earlier Millennium Development Goals in reducing poverty, hunger, and child death rates in Southeast Asia and Latin America but less so in Africa. Of course, opinions can, and do, differ about the probability that the transition towards a sustainable economy will largely succeed. However, the ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, which assumes no transition, is highly implausible. While the pathway and the speed of the transition are uncertain and may even be erratic, with failures along the way, the sustainable development agenda gives direction to thinking about the future. This book is about the role corporate finance can play in shaping this future and making production and consumption more sustainable via future-proof investment decisions.

The UN SDGs address challenges at the level of the economy, society, and the environment (or biosphere). Figure 1.3 illustrates the three levels and the ranking between them. A liveable planet is a precondition or foundation for humankind to thrive. A cohesive and inclusive society is needed to organise production and consumption to ensure enduring prosperity for all. In their seminal book Why nations fail, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) show that political institutions that promote inclusiveness generate prosperity. Inclusiveness allows everyone to participate in economic opportunities. Reducing social inequalities (SDG 10) is thus an important goal. Of course, there can be resource conflicts: unequal communities may disagree over how to share and finance public goods. These conflicts, in turn, break social ties and undermine the formation of trust and social cohesion (Barone & Mocetti, 2016; Berger, 2018).

1.2.2 System Perspective

While it is tempting to start working on partial solutions at each level, the environmental, societal, and economic challenges are interlinked. It is important to embrace an integrated social-ecological system perspective (Norström et al., 2014). Such an integrated system perspective highlights the dynamics that such systems entail, including the role of ecosystems in sustaining human well-being, cross-system interactions, and uncertain thresholds.

Holling (2001) describes the process of sustainable development as embedded cycles with adaptive capacity. A key element of adaptive capacity is the resilience of the system to deal with unpredictable shocks (which is the opposite of the vulnerability of the system). Complex systems feature adaptive cycles that aggregate resources and periodically restructure to create opportunities for innovation. However, some systems are maladaptive and trigger, for example, a poverty trap or land degradation (i.e., the undermining of the quality of soil as a result of human behaviour or severe weather conditions). Holling (2001) concludes that ecosystem management via incremental increases in efficiency does not work. For transformation, ecosystem system management must build and maintain ecological resilience as well as social flexibility to cope, innovate, and adapt.

1.2.2.1 Examples of Cross-system Interactions and Uncertain Thresholds

A well-known example of cross-system interaction is the linear production of consumption goods at the lowest cost contributing to ‘economic growth’ while depleting natural resources, using child labour and producing carbon emissions and other waste. In this book, we use carbon emissions as a shorthand for all greenhouse gas emissions, which include carbon dioxide CO2, methane CH4, and nitrous oxide N2O.

Another example of cross-system interaction is climate change leading to increasingly intense weather-related disasters, such as storms, flooding, and droughts. The low- and middle-income countries around the equator are especially vulnerable to these extreme weather events, which could damage a large part of their production capacity. The temporary loss of tax revenues and increase in expenditure to reconstruct factories and infrastructure might put vulnerable countries into a downwards fiscal and macroeconomic spiral with an analogous increase in poverty. Social and ecological issues are thus interconnected, whereby the poor in society are more dependent on ecological services and are less protected against ecological hazards.

An example of an uncertain threshold combined with feedback dynamics is the melting of the Greenland ice sheet. New research has found that it is more vulnerable to global warming than previously thought. Robinson et al. (2012) calculate that a 0.9 °C increase in global temperature from today’s levels could lead the Greenland ice sheet to melt completely. Such melting would create further climate feedback in the Earth’s ecosystem because melting the polar icecaps could increase the pace of global warming (by reducing the refraction of solar radiation, which is 80% from ice, compared with 30% from bare earth and 7% from the sea) as well as rising sea levels. These feedback mechanisms are examples of tipping points and shocks, which might happen.

Another example of cross-system interaction between several planetary boundaries is biodiversity loss. Box 1.4 shows the direct drivers of biodiversity loss.

Box 1.4: Direct Drivers of Biodiversity Loss

There are five direct drivers of biodiversity loss:

- 1. Climate change, where a change in climate destabilises ecosystems

- 2. Invasive species, where animals or plants have been moved to places where they damage existing ecosystems, e.g., Japanese knotweed

- 3. Land-use change, such as cutting down a forest to make way for agriculture

- 4. Overexploitation of natural resources, where a resource is used up faster than it can be replaced, e.g., overfishing

- 5. Pollution of air, land, or water, such as overuse of fertiliser containing phosphorus and nitrogen

Source: CISL (2021).

We cannot understand the sustainability of organisations in isolation from the socioecological system in which they are embedded: what are the thresholds, sustainability priorities, and feedback loops? Moreover, we should consider not only the socioecological impact of individual organisations but also the aggregate impact of organisations at the system level. The latter is relevant for sustainable development.

1.3 The Objective of the Company

To discuss the role of companies in sustainability, we first need to establish the objective of the company. The classical shareholder model in corporate finance argues that companies should maximise shareholder value (Jensen, 2002). In contrast, the stakeholder model argues that large companies should act in the interests of financial as well as social stakeholders and optimise stakeholder value (Magill et al., 2015). The integrated model states that companies should optimise integrated value, which combines financial, social, and environmental value (Schoenmaker & Schramade, 2019). The choice of the value maximisation function has consequences for decision-making on corporate investment.

To classify the different corporate finance models, Fig. 1.4 shows our framework for managing sustainable development. At the level of the economy, the financial return and risk trade-off is optimised. This financial orientation supports the idea of profit maximisation by companies. Next, at the societal level, the impact of investment and business decisions on society is optimised. Finally, at the level of the environment, the environmental impact is optimised. As we have argued in Sect. 1.2, there are interactions between the levels. It is thus important to choose an appropriate combination of the financial, social, and environmental aspects.

...

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-35009-2_1#Tab2

Cách để tải tài liệu.

1. Nếu bạn ĐÃ CÓ tài khoản: Vui lòng Tải về để xem chi tiết

2. Nếu bạn CHƯA CÓ tài khoản: Vui lòng xem hướng dẫn TẠI ĐÂY

Mọi thắc mắc vui lòng liên hệ: 0917 267 397